Hemianopsia test: methods and examination instruments

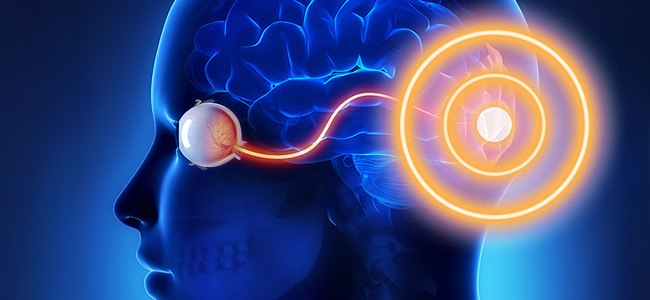

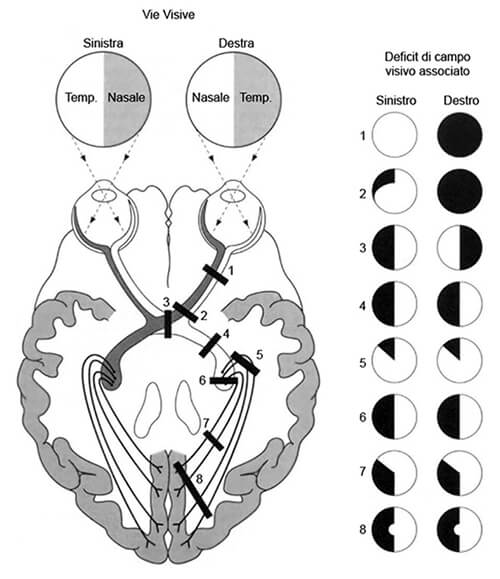

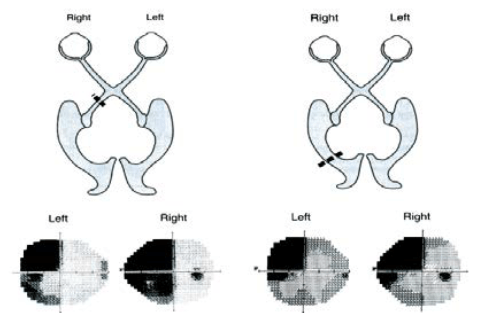

The term hemianopsia refers to the loss of conscious vision, in a specific portion of the visual field, resulting from a lesion in the primary visual pathway. In particular, the hemianoptic disorder may depend on a lesion along the pathway from the retina through the lateral geniculate nucleus (NGL) to the visual cortex (see Figure 1).

The characteristics of the visual disorder are determined by the location of the damage, which defines the affected quadrant or visual hemicampus.

The deficit affects a part of the space in the visual field contralateral to the lesion so that after right brain damage there will be hemianopsia affecting the left visual hemicampus and vice versa.

Left homonymous hemianopsia is among the most frequent after post-chiasmatic brain damage and the most common cause of this symptomatology in adults is stroke, followed by other aetiologies (causative agents) such as traumatic brain injury or brain tumors.

People with hemianopsia do not scan the visual field correctly and do not spontaneously use effective compensatory visual search strategies. The main difficulty concerns visual-spatial exploration, which is slow and disorganized.

In most hemianopsia subjects, oculomotor scanning (visual scanning) is impaired in both the blind and healthy visual fields, although the impairment is particularly pronounced in the blind field.

Hemianopsia: Limitations in daily life

These impairments translate into major limitations in activities of daily living: disorientation, falls, and bumping into obstacles in dynamic situations are common. People with hemianopsia have difficulty orienting themselves in space or finding objects in the damaged part of the visual field.

In addition, everyday difficulties vary depending on the condition of the visual field: for example, with a loss of the lower part of the visual field, one has more difficulty climbing stairs than with a loss of the upper part. The impairment causes problems in judging distances, orienting oneself in a crowd, or crossing the street in traffic.

In addition, this condition incapacitates driving a vehicle and limits the person’s autonomy. Thus, hemianopsia results in severe psychological distress and has significant repercussions on the psychophysical well-being of hemianopia patients.

Assessment and tools for investigating hemianopsia

The assessment of hemianopsia disorder is a complex process aimed at identifying the subject’s symptom profile and setting up an effective intervention treatment that aims to reduce difficulties and counteract limitations due to the deficit.

In general, the difficulty of visual exploration presents itself differently in the various types of hemianopsia, which is why, to be able to make a correct interpretation, a consistent battery of tests and methodologies is required to help differentiate the diagnosis.

Among the diagnostic methods commonly used to systematically test the visual field are

- neuropsychological examination involves the use of specific tests such as campimetry, or perimetry

- pen-and-paper tests and tests to investigate attention and visual-spatial exploration.

In addition, the functional assessment of the deficit is supported by instruments such as the ophthalmometer, or eye-tracker, which allows us to assess the effectiveness of the saccades, the most frequent eye movements.

Campimetry: the visual field examination

In detail, during campimetry, the subject is asked to identify, while holding their gaze in central fixation, luminous stimuli of varying intensity presented at different positions in the visual field.

Generally, perimeters are used for each eye to obtain a full representation of the spared and injured parts of the visual field.

In the case of left hemianopsia, for example, campimetry shows a spatially circumscribed visual deficit, independent of the nature of the stimulus, with areas of vision (in white) and others (in black) showing the extent of the deficit (see figure 2).

Visual exploration tests assess the ability to visually search for a target among distractors and can be performed with various protocols. The subject may be asked to recognize letters or name numbers projected onto the visual field in random order.

Eye trackers of the visual path: reading tests

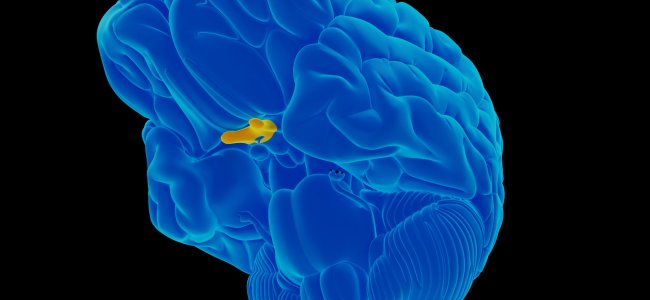

Using the coulometer, on the other hand, an individual’s eye activity can be analyzed and an objective measurement of the visual pathway can be obtained.

Visual-spatial exploration tests, combined with the recording of eye movements with the ophthalmometer, make it possible to assess how organized and strategic the exploration of the visual field is.

Compared to the norm, evaluations of hemianopsia subjects document alterations in spatial and temporal parameters in visual search tasks; oculomotor behavior is characterized by non-regular saccades and an increased number of fixations that increase visual scanning times.

Consequently, visual exploration is ineffective and seems to explain the subjective difficulties complained of, such as those related to reading.

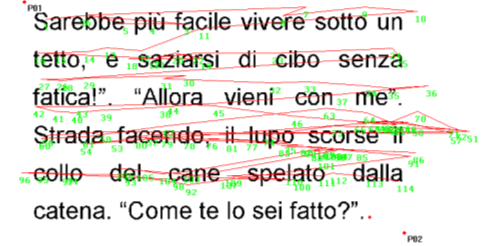

The reading tests show high execution times, poor accuracy, and deficient oculomotor parameters (see Figure 3).

Specifically, right-handed hemianopsia presents prolonged fixations with hypermetric saccades to the right and have difficulty in reading direction and line exploration.

On the other hand, left-handed hemianopsia presents difficulties in moving to the next line.

The functional assessment of hemianopsia

The functional assessment of the hemianopsia disorder allows the person’s oculomotor profile to be framed, which is useful for identifying and implementing an effective rehabilitation intervention.

Thanks to specific training for visual field disorders, residual visual abilities can be expanded and enhanced through systematic practice of saccadic movements and audio-visual stimulation of the blind hemicampus.

Thus, by exploiting mechanisms of brain plasticity and multisensory integration, compensatory functions such as appropriate oculomotor strategies can be reinforced.

In conclusion, as the spontaneous recovery of the visual field only occurs in a small percentage of people, the assessment pathway and rehabilitation care are crucial to reduce the degree of disability and improve the quality of daily life.

Bibliography

- B. L. Zuber, J. L. Semmlow, and L. Stark, “Frequency Characteristics of the Saccadic Eye Movement,” Biophys. J., vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 1288–1298, 1968.

- Bowers, Alex R., Egor Ananyev, Aaron J. Mandel, Robert B. Goldstein, and Eli Peli. 2014. “Driving with Hemianopia: IV. Head Scanning and Detection at Intersections in a Simulator.” Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 55 (3): 1540–48. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12748.

- C. Perez and S. Chokron, “Rehabilitation of homonymous hemianopia: insight into blindsight,” Front. Integr. Neurosci., vol. 8, no. October, pp. 1–12, 2014.

- Chedru, F., M. Leblanc, and F. Lhermitte. 1973. “Visual Searching in Normal and Brain-Damaged Subjects (Contribution to the Study of Unilateral Inattention).” Cortex 9 (1): 94–111.

- Elgin, Jennifer, Gerald McGwin, Joanne M. Wood, Michael S. Vaphiades, Ronald A. Braswell, Dawn K. DeCarlo, Lanning B. Kline, and Cynthia Owsley. 2010. “Evaluation of On-Road Driving in People with Hemianopia and Quadrantanopia.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association 64 (2): 268–78. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.64.2.268.

- Facchin, A., & Daini, R. O. B. E. R. T. A. (2015). Deficit centrali di campo visivo. Platform Optic, ottobre.

- Felten, D. L., & Maida, M. S. (2017, March). Atlante di neuroscienze di Netter. Edra.

- G. Kerkhoff, “Restorative and compensatory therapy approaches in cerebral blindness – a review,” Restor Neurol Neurosci, vol. 15, no. 2–3, pp. 255–271, 1999.

- G. Vallar and C. Papagno, Manuale di neuropsicologia, Terza ed. Bologna: il Mulino, 2018.

- Goodwin, D. (2014). Homonymous hemianopia: challenges and solutions. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 8, 1919.

- Goodwin, D. (2014). Homonymous hemianopia: challenges and solutions. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 8, 1919.

- Grunda, T., Marsalek, P., & Sykorova, P. (2013). Homonymous hemianopia and related visual defects: Restoration of vision after a stroke. Acta neurobiologiae experimentalis, 73(2), 237-249.

- Ishiai, Sumio, Tetsuo Furukawa, and Hiroshi Tsukagoshi. 1987. “Eye-Fixation Patterns in Homonymous Hemianopia and Unilateral Spatial Neglect.” Neuropsychologia 25 (4): 675–679.

- J. N. Carroll and C. A. Johnson, “Visual Field Testing,” 2013. [Online]. Available: http://eyerounds.org/tutorials/VF-testing/.

- J. Otero-Millan, X. G. Troncoso, S. L. Macknik, S. MartinezConde, and I. Serrano-Pedraza, “Saccades and microsaccades during visual fixation, exploration, and search: Foundations for a common saccadic generator,” J. Vis., vol. 8, no. 21, pp. 1–18, 2008.

- Kandel, E., Schwartz, J., Steven, T. M., Siegelbaum, A., & Hudspeth, A. J. (2014). Principi di neuroscienze (IV). Milano: Casa Editrice Ambrosiana.

- Làdavas, E. (2012). La riabilitazione neuropsicologica. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Làdavas, E., & Berti, A. (2014). Neuropsicologia. Bologna: Il mulino.

- M. Rolfs, “Microsaccades: Small steps on a long way,” Vision Res., vol. 49, no. 20, pp. 2415–2441, 2009.

- N. M. Dundon, C. Bertini, E. Làdavas, B. A. Sabel, and C. Gall, “Visual rehabilitation : visual scanning , multisensory stimulation and vision restoration trainings,” vol. 9, no. July, pp. 1–14, 2015.

- Passamonti, C., Bertini, C., & Làdavas, E. (2009). Audio-visual stimulation improves oculomotor patterns in patients with hemianopia. Neuropsychologia, 47(2), 546-555. Zhang et al. 2006

- PRISMA – Bollettino Di Aggiornamento Dell’associazione Italiana Ortottisti Assistenti In Oftalmologia. Spedisce: Centro Organizzazione e Congressi, via Miss Mabel Hill 9, 98039, Taormina, Anno 2013, Numero 2

- S. Pannasch, M. Joos, and B. M. Velichkovsky, “Time course of information processing during scene perception: The ii relationship between saccade amplitude and fixation duration,” Vis. cogn., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 473–494, Apr. 2005.

- S. Schuett, “The rehabilitation of hemianopic dyslexia,” Nat. Rev. Neurol., vol. 5, no. 8, pp. 427–437, 2009. [16] T. M. Schofield and A. P. Leff, “Rehabilitation of hemianopia,” Curr. Opin. Neurol., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 36–40, 2009.

- Zhang, X., Kedar, S., Lynn, M. J., Newman, N. J., & Biousse, V. (2006). Homonymous hemianopia in stroke. Journal of Neuro-ophthalmology, 26(3), 180-183.

- Zihl, J. (1995a). Visual scanning behavior in patients with homonymous hemianopia. Neuropsychologia, 33(3), 287-303.

- Zihl, J. (1995b). Eye movement patterns in hemianopic dyslexia. Brain, 118(4), 891-912.

You are free to reproduce this article but you must cite: emianopsia.com, title and link.

You may not use the material for commercial purposes or modify the article to create derivative works.

Read the full Creative Commons license terms at this page.