Hemianopsia and Neglect: the differential diagnosis

The differential diagnostic process applied to hemianopsia and Neglect involves a thorough evaluation of neurological symptoms and signs, particularly visual, cognitive, behavioral, and motor aspects.

In addition, it may be useful to subject the patient to neuropsychology testing to assess cognitive functions, such as memory, attention, verbal comprehension, spatial orientation, and visual perception. Once a proper diagnostic process has been carried out, the physician can make the diagnosis, prescribe appropriate treatment, and schedule rehabilitation.

In the neural rehabilitation pathway, it is crucial to distinguish the diagnosis accurately, even in more complex situations such as those of hemianopsia and unilateral spatial neglect or state of neglect.

Fundamental to the diagnosis

After brain injury, neglect and hemianopsia are common disorders that are often confused due to the complexity of symptoms and affect the temporal visual field. In these cases, it is essential to use specific diagnostic and rehabilitation tools, such as tests for hemianopsia, visuospatial function assessments, spatial orientation tests, memory tests, and other instrumental tests such as electroencephalogram or MRI.

The use of these tools allows for a more accurate differential diagnosis and better management of the neural rehabilitation process. Differential diagnosis can be difficult because both conditions cause difficulties in perception and reaction to stimuli in the contralesional half-space, both in testing and in daily life. Moreover, it is not uncommon to find the coexistence of both disorders, which makes symptom management even more complex.

For this reason, it is essential to conduct a thorough evaluation of symptoms and, if possible, perform instrumental tests to help identify the cause of the disorder and determine the appropriate treatment. Once a diagnosis has been made, appropriate treatments for hemianopsia or neglect can be selected. These treatments may include the use of rehabilitation techniques such as visual perception exercises, cognitive activities, cognitive behavioral therapy, etc. In addition, drug therapy may help manage the symptoms of optic tracts.

A complex clinical condition

By definition, hemianopsia depends on the damage to the primary visual pathway and is manifested by a deficit in a portion of the visual field opposite the lesion, distinguished by a loss of vision in a specific portion of space. Thus, after right brain damage, hemianopsia will affect the left visual hemicampus and viceversa.

In neglect, the deficit is also contralateral to the brain injury, but different. The main cause of the pathology is a lesion usually associated with the right hemisphere. The deficit is defined by the loss of awareness of the space opposite the lesion, whereby, one will no longer have awareness of stimuli coming from the left, a true loss of half of the visual field.

Specifically, neglect is a reduced tendency to pay attention to, perceive, and interact with stimuli (visual, auditory, and tactile) from the hemispace contralateral to the lesion.

This complex clinical condition, depending on the brain area affected, can present in multiple modalities: visual, auditory, motor, word-only, perceptual, or perceptual but not exploratory. In the latter, in particular, the disease is characterized by blindness with unconscious perception, that is, the unconscious brain mechanism continues to record and analyze objects in neglected space even though they fail to be brought to consciousness.

Among its various forms, visual neglect is commonly placed in differential diagnosis with hemianopsia visual field disorder, to compare the aspects that most unite the two clinical conditions.

Differences in neuropsychological assessment

During the neuropsychological assessment, cognitive domains such as attention and visuospatial exploration, body space exploration, or reading are investigated. In addition, people undergo examinations such as Computerized Visual Range or campimetry to assess the extent of visual impairment. Generally, to measure awareness of the disorder and the severity of the disability in daily life, questionnaires and scales assessing the impact and perception of the deficit in individuals are also submitted during an eye examination.

The performances of the two clinical populations denote two symptomatologies that differ on several points. The first basic difference is the extent of the visual deficit, which in hemianopsia, but not in neglect, directly affects the primary visual pathway.

Campimetries show a constant difficulty in patients with hemianopsia, regardless of the stimulus presented and evident in a defined right or left space. Whereas, in neglect, cabinetries detect an inconstant, non-spatially defined deficit in which stimuli of different natures can induce variable performance.

One difference between hemianopsia patients and those with neglect is that the former exhibit disorganized visual exploration and tend to scan both the intact and impaired visual field, whereas subjects with neglect explore the healthy visual field more intensively and the neglected field little or not at all. This happens because hemianopsia is aware of their difficulties, unlike subjects with neglect who are anosognosic and therefore have no awareness of their deficit.

In neglect, one of the main problems is that the disability perceived by the subject is different from that observed by family members.

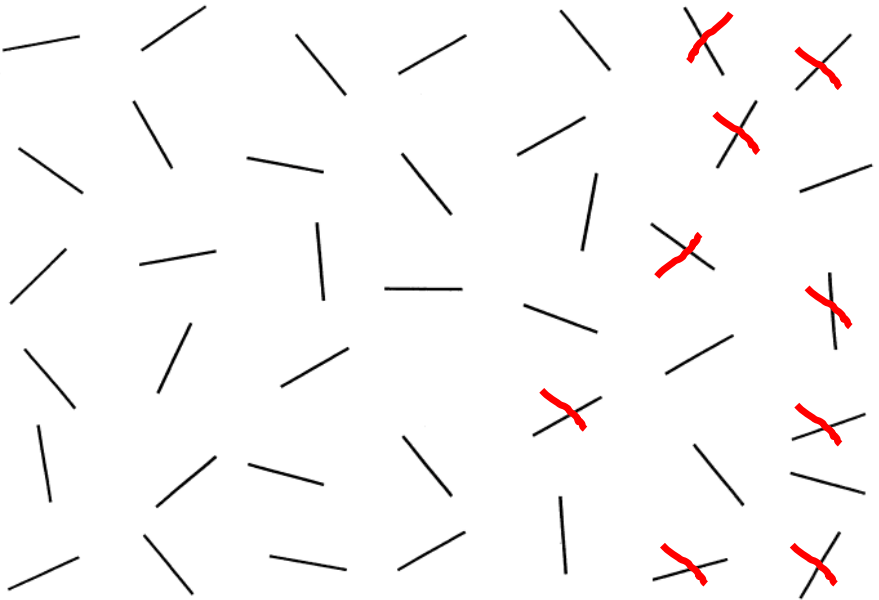

Another example of tests most commonly used in neuropsychological evaluations of these symptoms is the Deletion Test in which people are asked to cross out all stimuli randomly distributed on a sheet.

Differences in performance and tests used

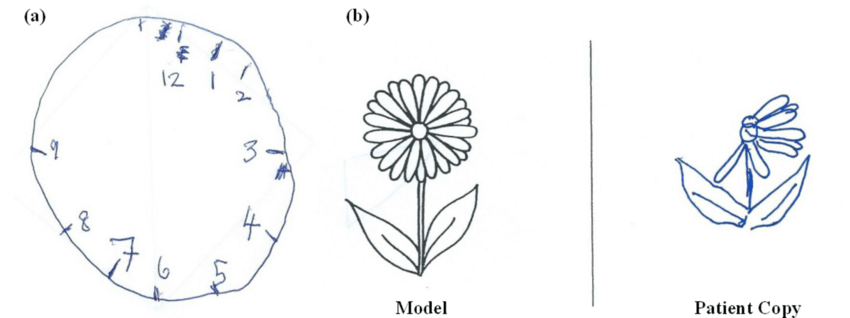

Tests can be presented in various ways (lines, letters, stars) and differ in type, density, and presence of distractors. During erasure tests, few omissions are generally observed in hemianopsia compared with subjects with visual neglect, where omissions in the affected space are numerous and often associated with perseverations (fig.1).

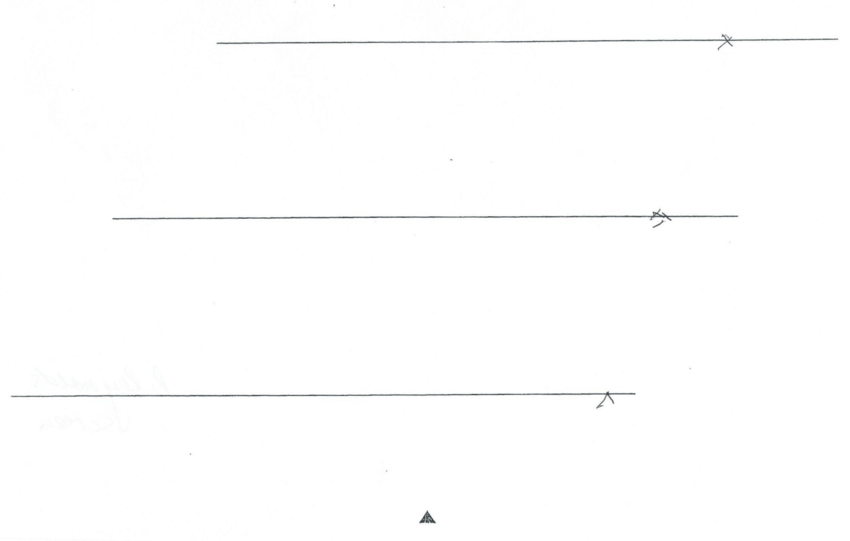

In line bisection tests, on the other hand, people are asked to draw a perpendicular line that divides the various horizontal lines presented in the paper in half.

The bisection is correct in hemianopsia with a possible deviation toward the blind field; whereas, in neglect, the bisection deviates toward the healthy field because patients tend to move the midpoint to the right (fig.2).

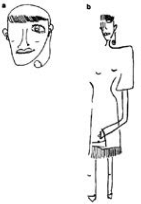

Another widely used task is the copying of simple figures, in which, patients with neglect, compared to hemianopsia, are more impaired and omit the left parts with an obvious imbalance.

Spontaneous Drawing Tests are useful in determining whether there are signs of representational neglect. This can be detected through omissions, distortions, or spatial transpositions from the left side. (fig. 3 e 4).

Reading tests also reveal different problems, such as errors by hemianopia and slow reading by individuals with neglect, which include errors in reading single words and omissions of the left column.

In addition, studies have shown that the use of ecological testing is an excellent way to identify neglect.

The Behavioral Inattention Test (BIT, Fig. 5) is a complex battery of tests that can identify neglect conditions and differentiate them from others. This type of test can also help build a behavioral profile of the patient, allowing a better understanding of his or her situation.

In conclusion

To ensure sufficient stability and to ensure that performance is correctly interpreted, assessment must make use of consistent testing and evidence that assesses the different levels at which impairments may emerge. In both clinical conditions, disability reflects obvious difficulties in daily life; therefore, it is important to clarify the diagnoses and intervene appropriately.

It is important to recognize that some standard tests may not be able to accurately identify neglect. Therefore, more complex and realistic tests have been developed that can help identify neglect with standard and ecological tests.

For example, the Behavioral Inattention Test provides a useful behavioral profile of the patient to differentiate his or her condition from others. In addition, to ensure proper interpretation of results, it is important to use tests that assess the different levels at which disorders may emerge.

Bibliography

- B. L. Zuber, J. L. Semmlow, and L. Stark, “Frequency Characteristics of the Saccadic Eye Movement,” Biophys. J., vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 1288–1298, 1968.

- Bowers, Alex R., Egor Ananyev, Aaron J. Mandel, Robert B. Goldstein, and Eli Peli. 2014. “Driving with Hemianopia: IV. Head Scanning and Detection at Intersections in a Simulator.” Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 55 (3): 1540–48. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12748.

- C. Perez and S. Chokron, “Rehabilitation of homonymous hemianopia: insight into blindsight,” Front. Integr. Neurosci., vol. 8, no. October, pp. 1–12, 2014.

- Chedru, F., M. Leblanc, and F. Lhermitte. 1973. “Visual Searching in Normal and Brain-Damaged Subjects (Contribution to the Study of Unilateral Inattention).” Cortex 9 (1): 94–111.

- Elgin, Jennifer, Gerald McGwin, Joanne M. Wood, Michael S. Vaphiades, Ronald A. Braswell, Dawn K. DeCarlo, Lanning B. Kline, and Cynthia Owsley. 2010. “Evaluation of On-Road Driving in People with Hemianopia and Quadrantanopia.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association 64 (2): 268–78. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.64.2.268.

- Facchin, A., & Daini, R. O. B. E. R. T. A. (2015). Deficit centrali di campo visivo. Platform Optic, ottobre.

- Felten, D. L., & Maida, M. S. (2017, March). Atlante di neuroscienze di Netter. Edra.

- G. Kerkhoff, “Restorative and compensatory therapy approaches in cerebral blindness – a review,” Restor Neurol Neurosci, vol. 15, no. 2–3, pp. 255–271, 1999.

- G. Vallar and C. Papagno, Manuale di neuropsicologia, Terza ed. Bologna: il Mulino, 2018.

- Goodwin, D. (2014). Homonymous hemianopia: challenges and solutions. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 8, 1919.

- Goodwin, D. (2014). Homonymous hemianopia: challenges and solutions. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 8, 1919.

- Grunda, T., Marsalek, P., & Sykorova, P. (2013). Homonymous hemianopia and related visual defects: Restoration of vision after a stroke. Acta neurobiologiae experimentalis, 73(2), 237-249.

- Ishiai, Sumio, Tetsuo Furukawa, and Hiroshi Tsukagoshi. 1987. “Eye-Fixation Patterns in Homonymous Hemianopia and Unilateral Spatial Neglect.” Neuropsychologia 25 (4): 675–679.

- J. N. Carroll and C. A. Johnson, “Visual Field Testing,” 2013. [Online]. Available: http://eyerounds.org/tutorials/VF-testing/.

- J. Otero-Millan, X. G. Troncoso, S. L. Macknik, S. MartinezConde, and I. Serrano-Pedraza, “Saccades and microsaccades during visual fixation, exploration, and search: Foundations for a common saccadic generator,” J. Vis., vol. 8, no. 21, pp. 1–18, 2008.

- Kandel, E., Schwartz, J., Steven, T. M., Siegelbaum, A., & Hudspeth, A. J. (2014). Principi di neuroscienze (IV). Milano: Casa Editrice Ambrosiana.

- Làdavas, E. (2012). La riabilitazione neuropsicologica. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Làdavas, E., & Berti, A. (2014). Neuropsicologia. Bologna: Il mulino.

- M. Rolfs, “Microsaccades: Small steps on a long way,” Vision Res., vol. 49, no. 20, pp. 2415–2441, 2009.

- N. M. Dundon, C. Bertini, E. Làdavas, B. A. Sabel, and C. Gall, “Visual rehabilitation : visual scanning , multisensory stimulation and vision restoration trainings,” vol. 9, no. July, pp. 1–14, 2015.

- Passamonti, C., Bertini, C., & Làdavas, E. (2009). Audio-visual stimulation improves oculomotor patterns in patients with hemianopia. Neuropsychologia, 47(2), 546-555. Zhang et al. 2006

- PRISMA – Bollettino Di Aggiornamento Dell’associazione Italiana Ortottisti Assistenti In Oftalmologia. Spedisce: Centro Organizzazione e Congressi, via Miss Mabel Hill 9, 98039, Taormina, Anno 2013, Numero 2

- S. Pannasch, M. Joos, and B. M. Velichkovsky, “Time course of information processing during scene perception: The ii relationship between saccade amplitude and fixation duration,” Vis. cogn., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 473–494, Apr. 2005.

- S. Schuett, “The rehabilitation of hemianopic dyslexia,” Nat. Rev. Neurol., vol. 5, no. 8, pp. 427–437, 2009. [16] T. M. Schofield and A. P. Leff, “Rehabilitation of hemianopia,” Curr. Opin. Neurol., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 36–40, 2009.

- Zhang, X., Kedar, S., Lynn, M. J., Newman, N. J., & Biousse, V. (2006). Homonymous hemianopia in stroke. Journal of Neuro-ophthalmology, 26(3), 180-183.

- Zihl, J. (1995a). Visual scanning behavior in patients with homonymous hemianopia. Neuropsychologia, 33(3), 287-303.

- Zihl, J. (1995b). Eye movement patterns in hemianopic dyslexia. Brain, 118(4), 891-912.

- Toraldo A, Romaniello C, Sommaruga P (2017). Measuring and diagnosing neglect: a standardized statistical procedure. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. DOI: 10.1080/13854046.2017.1349181.

- Hemispatial neglect: clinical features, assessment and treatment – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate.

- Hemispatial neglect: clinical features, assessment and treatment – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate.

You are free to reproduce this article but you must cite: emianopsia.com, title and link.

You may not use the material for commercial purposes or modify the article to create derivative works.

Read the full Creative Commons license terms at this page.