Hemianopsia and diseases of the optic chiasma

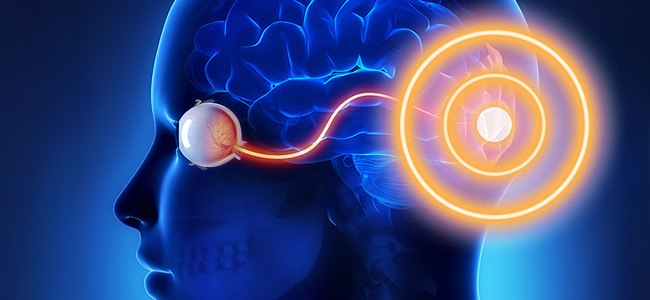

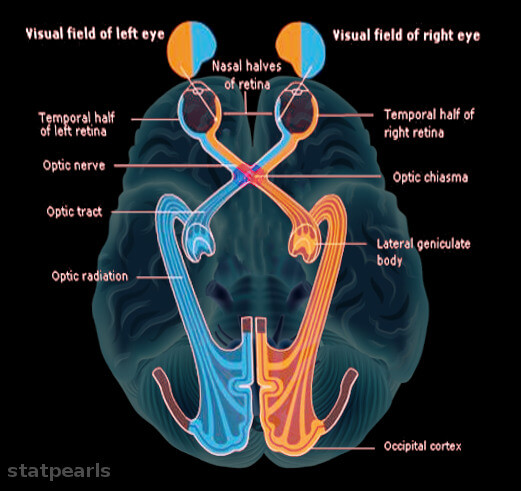

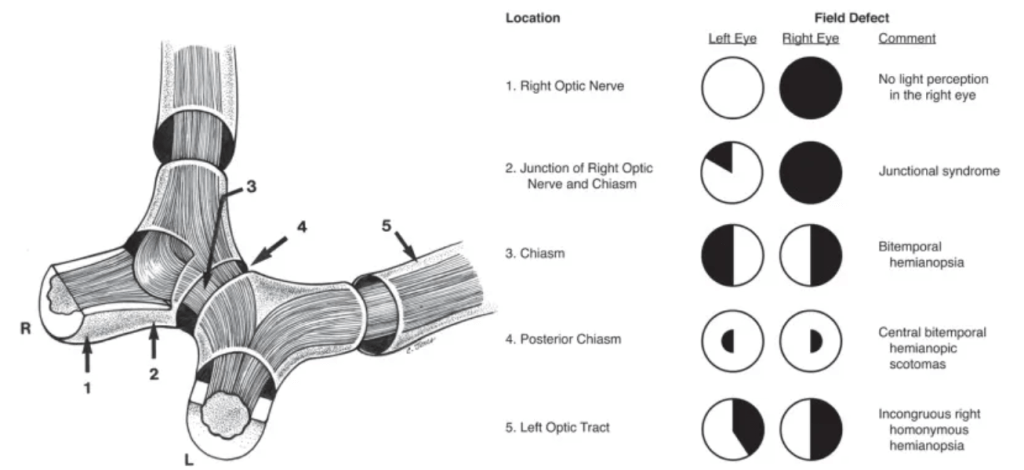

The optic chiasma originates from the union of the two optic nerves: at the level of the chiasma, the nasal fibers from each retina decussate (i.e. cross) and join with the temporal fibers from the retina of the other eye to form the two optic tracts that continue posterior to the chiasma; in this way, the fibers carrying information from the right visual field are led to the left side of the brain and vice versa (Fig. 1)

At the level of the optic chiasma, the peculiar arrangement of the fibers can be seen, with the crossing of those from the two nasal hemiretines. © 2023 StatPearls Publishing LLC

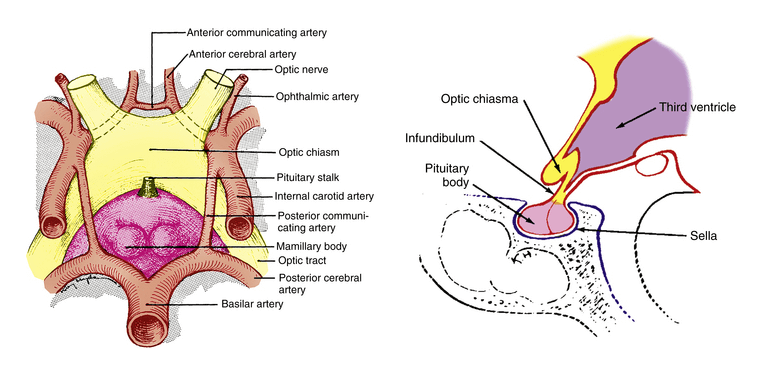

The chiasma, which is located below the frontal lobe of the brain, is adjacent to many important structures (Fig. 2): dorsally there is the floor of the 3rd ventricle and the hypophyseal peduncle, ventrally we have the sellar diaphragm and the chiasmatic sulcus, laterally the internal carotid arteries and the anterior cerebral arteries, laterally and inferiorly the cavernous sinuses. This area also includes the pituitary gland, located inferiorly to the chiasma.

Knowledge of the close relationship between the optic chiasm and these structures helps us understand the origin of possible chiasmatic lesions.

These lesions are manifested mainly by alterations in the patient’s visual field that reflect the peculiar distribution of fibers from the optic nerves already described; the most characteristic alteration is heteronymous hemianopsia, i.e. a deficit relative to half of the visual field seen by one eye and the opposite half of that seen by the other eye.

The certainly most frequent form is bitemporal hemianopsia (Fig. 3, case 3), with involvement of the outermost halves of the visual fields seen by the two eyes, corresponding to a cross-nasal fiber deficiency. The hemianopsia may begin mono-laterally and is often asymmetrical, possibly involving the lower or upper quadrants first and foremost depending on the direction of lesion expansion.

Image taken from Hoyt WF, Luis O (1963), The Primate Chiasm: Details of Visual Fiber Organization Studied by Silver Impregnation Techniques, Arch Ophthalmol, 70(1):69-85

Among the most frequent causes of this type of optic chiasm lesion are tumors: secreting and non-secreting pituitary adenomas, craniopharyngiomas, meningiomas, gliomas, and astrocytomas.

A much less frequent visual field defect is basal heteronymous hemianopsia by in teresting fibers from the temporal halves of the retinas.

Generally, the nasal defect occurs unilaterally, unlike temporal hemianopsias, and its possible causes are aneurysms of the internal carotid artery, chiasmatic infarcts, demyelinating lesions such as chiasmatic optic neuritis, or bilateral carotid stenosis.

Other possible causes and consequences of chiasmatic lesions

Other possible causes of chiasmatic lesions are aneurysmal dilatations of one of the polygon of Willis vessels, inflammations and infections (e.g. mucocele of the frontal sphenoid sinus, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, syphilis), head trauma (as in the case reported in article no. 1: a 50-year-old man who, following a car accident, suffered an extensive fracture from the right orbit to the sella turcica with consequent bitemporal hemianopsia) and the empty sella syndrome, linked to a herniation of the subarachnoid space within the sella turcica that can lead to a widening of the sella itself and a flattening of the pituitary gland.

The visual field alterations described above are typical of lesions of the central portion of the optic chiasm, but whether the lesion occurs more anteriorly or more posteriorly the outcome may be different:

- if the lesion is anterior, fibers from one eye may be involved before entering the chiasma and, on the same side, inferonasal fibers from the other eye, which are housed in the anterior portion of the optic chiasm. In this case, there will be a scotoma, often central, in the eye on the same side as the site of the lesion and a contralateral superotemporal defect and we speak in this case of a junctional scotoma (Fig. 3, case 2);

- if the lesion is posterior, the macular fibres, which decussate precisely in the posterior portion of the chiasma, are likely to be involved. In this case, a bitemporal paracentral perimetric defect arises (Fig. 3, case 4). If the lesion were to extend to the optic tract, it would also result in a homonymous hemianopsia contralateral to the side of the lesion (Fig. 3, case 5).

The article focuses on visual field alterations due to chiasmatic lesions; however, it is worth briefly listing other possible consequences:

- ocular and visual: reduction of visus, desaturation of perceived colours, pupillary hyporeflexia to light, set-torial or diffuse pallor of the optic papilla (especially if the lesion persists for some time), binocular diplopia and alterations of ocular movements due to paralysis of the III, IV or VI cranial nerve due to compression or invasion of the cavernous sinus and, sometimes, nystagmus in the case of suprasellar tumours;

- extra-ocular: headache, hydrocephalus (if the lesion compresses the third ventricle) and, in cases of se-serniated pituitary adenoma, endocrine dysfunction that varies depending on the hormone produced.

In conclusion

Lesions of the optic chiasm can cause various visual field alterations. The most common alteration is bitemporal heteronymous hemianopsia, which affects the outer halves of the visual fields of both eyes. Other less common forms include binaural heteronymous hemianopsia and junctional scotomas. Tumors are the most frequent causes of chiasmatic lesions, but aneurysms, infarcts, demyelinating lesions, and head trauma can also cause such disorders.

In addition to visual field alterations, other symptoms such as reduced visual acuity, color desaturation, pupillary hyporeflexia, pallor of the optic papilla, diplopia, headache, and endocrine dysfunction can also occur. Understanding these lesions and their effects is fundamental to diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Bibliography

- Resneck JD, Lederman IR (1981), Traumatic Chiasmal Syndrome Associated with Pneumocephalus and Sellar Fracture, Am. J. Ophthalmol., 92(2): 233-7

- Schiefer U, Isbert M, Mikolaschek E et al. (2004), Distribution of scotoma pattern related to chiasmal lesions with special reference to anterior junction syndrome. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 242, 468-477

- xHarrington DO (1981), The visual fields, ed 5, St Louis, Mosby

- Astorga-Carballo A, Serna-Ojeda JC, Camargo-Suarez MF (2017), Chiasmal syndrome: Clinical characteristics in patients attending an ophthalmological center, Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 31, 229-233

- Trevino R (1995), Chiasmal syndrome. J Am Optom Assoc, 66(9):559-7

- [1] Affiliazione: Minerva Vision Care (Siracusa) – email: meneghini@minervavisioncare.it

You are free to reproduce this article but you must cite: emianopsia.com, title and link.

You may not use the material for commercial purposes or modify the article to create derivative works.

Read the full Creative Commons license terms at this page.